|

|

There

are three plants that are an essential part of the Mexican household,

limon [lime, not lemon], papaya, and the trusty sabila [aloe

vera].

Every Mexican home that has some kind of

a piece of garden has an arbol de limones in it, a lime tree,

not a lemon tree. It is planted as a twig, nurtured lovingly,

and if it has not produced limones in four years, bows of red

yard are tied on its branches, as encouragement. Believe me,

it works.

Before I had Bertha

to tell me these things, we had two lime trees that were over

ten years old and had never sported even a flower bud. I couldn't

understand this. In Cuernavaca, my arboles de limon had blossomed

on schedule and given me limones all year without any problems,

and they were on a rooftop terrace, in pots. In Acapulco, plants

seemed testier, stubborn , sensitive to the extreme heat and

mugginess and salt air. Without offering anything to the household,

the limones had managed sneakily to become part of the landscaping,

soon blending in nicely with the height-staggered oleanders,

hibiscus and Cuña de Moises, a floral wall that effectively

hid Lobo's dogrun. In time we forgot that they were there at

all, until Bertha came. Before I had Bertha

to tell me these things, we had two lime trees that were over

ten years old and had never sported even a flower bud. I couldn't

understand this. In Cuernavaca, my arboles de limon had blossomed

on schedule and given me limones all year without any problems,

and they were on a rooftop terrace, in pots. In Acapulco, plants

seemed testier, stubborn , sensitive to the extreme heat and

mugginess and salt air. Without offering anything to the household,

the limones had managed sneakily to become part of the landscaping,

soon blending in nicely with the height-staggered oleanders,

hibiscus and Cuña de Moises, a floral wall that effectively

hid Lobo's dogrun. In time we forgot that they were there at

all, until Bertha came.

She spotted them immediately. As our cook,

she was delighted that she could just clip limones from the backyard

any time she needed them. It also encouraged her that these Gringos

were sensible householders enough to have planted them at all.

However, upon her nightly watering activities, she noticed that

nothing was happening or had ever happened to these limones in

their productive cycle... We told her the whole sad story, and

she told us about the bows.

We smiled politely. She tied the bows on

at once, using her daughter Martha's hair ribbons until she got

red yarn at Gigante later in the day. Red yarn was absolutamente

necesario, y es mejor lana, que acrilico.

Bertha watered every evening, picking out

garden detritus, patting and smoothing everything in its turn

and giving the recalcitrant limones personal peptalks. Every

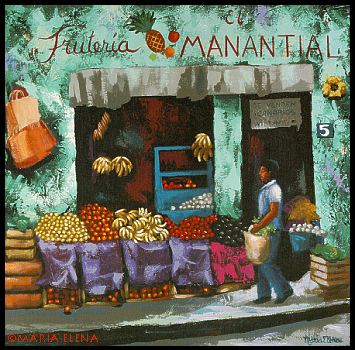

day she bought our limones fresh from the little street mercado

in Icacos.

There isn't a Mexican dish that doesn't

have a schpritz of lemon in it, even chicken soup. Try it. Everything

is garnished with sliced limon, even your morning fruit, limones

that are sliced in a special way so that you won't get it in

the eye and start your day out wrong, the way they slice them

in the cantinas. After all, ceviche is really only lime soup

with a lot of stuff in it. Bertha's fish fillets, sauteed in

equal portions of lime juice and butter with salt and pepper,

is not to be equaled.

Bertha was waiting for us one morning at

the bottom of the stairs instead of in the kitchen. She led us

first to the diningroom, where our waiting sliced papaya was

overwhelmed with sliced limones. Then around the pool to the

lime trees which were proudly fluttering not only with red bows,

but white blossoms, looking very pretty. Lobo eyed us from behind

the oleanders, his wagging tail gently wafting the scent of limon

blossoms at us. Bertha smiled. "Limones pronto", she

said, in the pidgin Spanish she reserved only for the Señor.

Ray loved Acapulco and had bought the house back in 1946 when

the Costera didn't even go out that far. He had never learned

Spanish, probably because he only used the house a month every

year, but Bertha thought that it was an unforgivable affront.

However Ray could sing "Como Te Quiero, De Veras" very

romantically. I sometimes wondered who had taught him.....

Bertha and Ray had a permanent armed truce

going. She considered that I had lived more happily and completely

before I got married. After all, I had had her to take care of

me. This was before she became a cocinera, and was still a recamarera,

a level up from being a muchacha. I would have designated her

as an Ama de Casa, since she took care of everything. She felt

sorry for me because I had been a pintora famosa and was now

just an appendage to a Señor. Bertha had had a tough time

with Señores. She thought she had gone up in the world

but I had gone down. She may have been right, but it didn't bother

me any.

Bertha had cured my conjunctivitis after

the doctor couldn't seem to get his act together, with a few

days of squirting lime juice in my eyes in the morning. I'd had

conjunctivitis for three months. Ray had a fit. Then Lobo had

one of our seven-pound toads spit in his face, getting their

poison in his eyes [that's what they aimed for, they knew it

was blinding]. Only Bertha knew what was happening to Lobo, who

was screaming like a human, tearing around the garden, banging

into palm trees and finally landing in the pool. She tore out

of the kitchen with a knife, grabbed a handful of limones and

ran right into the pool after the poor dog, cutting up lemons

on her way. She yelled at me to hold onto him so I jumped in

too, Ray furious because we were in the pool with our dirty shoes.

I grabbed Lobo by the ears and held on for dear life while she

squeezed lime juice into his eyes, time after time. Finally we

all trooped dripping into the kitchen to wash the chlorine and

acid from the pool out the poor dog's eyes. He refused to be

dried off and retired to his oleander grove to think . Lobo never

sniffed at another toad. I was as amazed at this as Ray since

we never had such uncivilized things as grossly overweight poisonous

toads in Cuernavaca. We were all greatly indebted to Bertha and

her limones. Bertha also used limones as an antiseptic, as an

astringent for acne and other problems, for brushing your teeth

[rub your teeth and gums hard with sliced limes and rinse your

mouth with lime water, an old naval solution for scurvy]. Rub

lime slices over your mosquito and other bug bites. Wash your

face with lime water, like the princesses of old. Even hives

feel better in a cool bath of lime water. People swear that a

cup of lime tea with honey every morning slims you down and keeps

the weight off.

Shortly after we had all the limones that

anyone could possibly want, Bertha turned her attentions to the

papaya trees, another essential to the Mexican household. We

had a real problem there. We always hoarded the seeds from the

best tasting breakfast papayas and planted them in coffee cans.

The hardiest growths were taken out and planted against the east

wall of the garden, the most sheltered spot, usually about four

a year. After two years they were big enough to bear fruit, but

they were unfortunately also big enough to attract the attention

of the ocean winds. Another thing I never had to worry about

in Cuernavaca. Papaya trees are tall and anorexical, with very

short roots. You can lean on a papaya tree and cause it grave

harm. They are greatly overloaded in life by a great mop of floppy

leaves and papayas bigger and heavier than footballs. They do

not bend with the wind like palm trees, they just lie down and

die, usually in the pool. We have hurricanes almost every year

in Acapulco and they are a great decimator of papaya trees, ours

included. After chopping off the tops and the root base, the

gardener would trudge up the ejido mountain to the left of Las

Brisas with the trunk, taking it home. I don't know what he did

with them.

Earlier we had him cut down nine elderly

palm trees that towered over the property, and I do know what

he did with them. These palms rained down general destruction

in the gardens with their deadly coconuts, exploding pots and

squashing plants and causing nervous terror during parties. Over

the years young men came to the door asking if we wanted the

palm trees cleared, they would do it for the coconuts, but as

time went on the young men found other more lucrative careers,

and another art form declined.

The gardener and the three friends who

had helped cut the trees down lugged eight of the trunks up the

hill to Las Brisas, where they were sold as roof poles. A good

ancient palm tree with no curve was treasured because it was

hard and thin and immune to termites, the scourge of Acapulco.

You could sit and watch your furniture disintegrate before you

if it was made of anything but cedar. The ninth tree pole went

up in our new palapa house by the pool. The little three-walled

house/bar was a trade for the poles, and was constructed by the

gardener and his Group of Three. A cambalache. They brought down

thatch from their hills, also skinnier poles and binding materials.

Not a nail in it.

We asked the Señor to batten down

our threatened papaya trees with ropes and screws on the walls,

since they were in a corner of the garden. He declined. So we

planted banana trees around them, as ground support. That didn't

work either. Well, after three years of picking papaya trees

and their accompanying mud and sludge out of the pool, we gave

up. After all, the mercado of Icacos was just down the street

and Bertha started buying them there. It was a lot less trouble.

The State of Guerrerro is the only place

that has the red papaya which taste like a mixture of Junket,[

that certainly dates me] and perfume. They are greatly prized

by Mexicans who take them home tied to tops of their cars along

with coconuts when they are on their way home to Mexico D.F.

There are dozens of little shacks and tiendas lining the first

ten miles on the highway out of Acapulco, selling both papaya

and coconuts, coconut candy and such.

Try papaya with a little limon sprinkled

over the slices in the morning. Nowadays chefs are concocting

great salsas with finely chopped papaya as sort of an extender,

giving it an interesting twang and, incidentally, calming down

the picante content. Besides being full of digestive enzymes,

they are a delight, a special taste. In most of Mexico you can

find papaya ice cream, don't miss it

Save the seeds, and plant them, if you

live in a warm climate that doesn't have a storm pattern. There

is really nothing a papaya tree or its friends can do about ocean

winds.

Our third plant necessary to the Mexican

household is a sabila [Aloe Vera]. Every home, even apartment

dwellers, has a sabila plant, usually years old, near the kitchen

door. It usually has several descendants in pots here and there

around the garden or courtyard, and in the houses of the descendants

of its owner. One of these pots of sabila is always placed by

the front door at Christmastime and festooned with -guess what?-

little red bows of red yard, mejor lana, que acrilico. I have

a potted sabila sitting by my sliding patio door right now, resplendent

in red bows with a few lightweight golden balls here and there.

America del Norte is not kind to the noble sabila, it is too

cold, too wet. Like the Bougainvillea, it craves sunburn and

thirst. Carefully brought into the house for the winter, away

from the incompatibilities of the Willamette Valley, I never

once thought of stashing it in the garage. It needs to be talked

to.

These sabila plants are friends to all

householders and Mexicans have known it since before Cuauhtemoc.

They slice open the leaves and use them as poultices for infections,

to soothe cuts and burns and grow new skin, for eczema, teenagers

skin disasters, age wrinkles, sunburns, lesions, sunspots and

skin tags, the list is endless. People take sabila internally

now, in capsule form, and there countless formulas for it in

skin creams and cosmetics. Sabila somehow encourages cellular

reconstruction.

I had two massive sabilas in my studio,

or rather, outside it, beside my front door and my back door.

They had snaked up and down the torturous mountain highway to

Acapulco years ago, along with various other plants I couldn't

part with, a big truckful. They came from Cuernavaca, six thousand

feet of Eternal Springtime up in the air, down to a muggy, mouldy

tropical climate that wilted most plants and people, and they

took it in their stride, all of them. They were all in big pots

and were in their new cosmic space around the pool by the end

of the day. Too bad I didn't take the limon trees. Now, a few

years later, they were trucked over to Ray's house.

When they arrived, Ray asked what in the

world I had brought "these" for. The two sabilas. He

thought you made Tequila out of them. With a certain ceremony

Bertha and I put one sabila by the front entrance and the other

by the kitchen door, where they settled down comfortably. Then

Bertha and I began extolling their virtues. So Ray took off a

sock and showed us his famous sunburn. Months ago, during one

of his beachwalks, he had somehow burned the arch of one foot

and not the other, and it had never healed. He started wearing

sox, partly to hide and keep clean the suppurating mess, and

partly as a defense tactic for nosey me. "O.K.,Bertha, heal

that", he said. "Si, Señor", she said,

and four days later, it was growing new skin.

Years before, my son Federico, and I went

to Relaciones Interiores in Mexico D.F. to get him a Mexican

passport. [He already had an American one, having been registered

for it on the day he was born.] We were on our way to a show

in Costa Rica. After lunch, walking along dirty Calle Victoria,

Federico, being twelve, dribbled his fingers along one of the

rotten walls, encrusted with forty coats of paint and crud and

caught himself a monster splinter. Four days later his finger

had a monster infection, the day before we were going to leave

by LACSA. We had to go, the paintings were already in San Jose,

and there was no way I could leave him in Cuernavaca. The only

thing I could think of was to lop off four sabila leaves, wrap

them airtightly in silver foil, and take them with us, hoping

Aduana would have no trouble with that. That night Federico went

to bed with his finger and arm [up to that nasty little blue

line] wrapped tightly around sliced sabila. He complained slightly

about the strange smell but was too sick to take it to court.

In the morning, fever and the blue line gone, I put a small poultice

around his finger and off we went, sabilas packed.

In San Jose, I changed the poultice and

put the rest of the sabila in the refrigerator, and, leaving

Federico in the sack, went on to the Cultural Institute to see

if my paintings were out of Aduana. We used a sabila a day, changing

the dressing morning, noon and night, and when the last of the

four was used up, his finger was fine. Federico and I were very

impressed. So was the maid, who actually asked me, What was this

porqueria that I was throwing out? Evidently they're behind the

times on sabilas in Costa Rica, or maybe the Aztecs never got

that far.

Once the sabila is cut open and the air

gets to it for a while, the flesh will turn red. Don't be shocked,

it's still fine to use it. Also, it does have a strange odor,

not bad, just unidentifiable. It goes away with a wash. I think

you have less trouble with the sabila than any other plant in

the world, and it certainly gives more back to man than any other

plant in the world.

So these three plants are the dietary and

first aid box gifts of nature and should be growing happily in

your garden or in a pot somewhere, at the ready. Use them in

good health. I hope you have a terrace or a garden where you

can fit them in. If not, plan your next move around them. You'll

be glad you did. |